Blueberry

General description

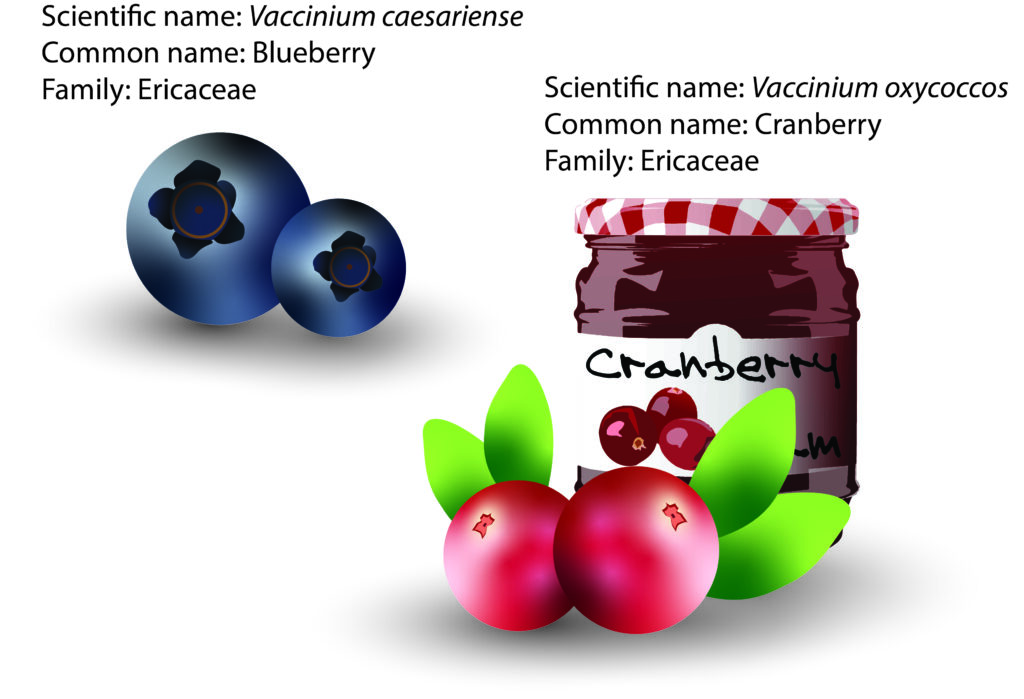

Blueberries belong to the genus Vaccinium in the health family Ericaceae. They are classified in the Cyanococcus section within the genus Vaccinium. Several sections are agriculturally important, including Cyanococcus (true blueberries), Oxycoccus (cranberries), and Myrtillus (bilberries and whortleberries). Wild representatives of Oxycoccus and Myrtillus are found in Europe and North America, while Cyanococcus is solely in North America. This is a large and varied genus of about four hundred and fifty species of deciduous and evergreen shrubs and occasionally small trees and vines. Both wild (lowbush) and cultivated (highbush) commercially produced are all native to North America.

The species seen in the garden are shrubs valued for their edible berries or their striking fall color. The berries, known according to the species as lingonberry, bilberry, blueberry, cranberry, huckleberry, or whortleberry, are red or blue-black and often covered with a ripe bloom. They are grown commercially for fresh fruit, as well as for juicing and canning. Vacciniums are indigenous mainly to the northern hemisphere in many habitats, stretching from the Artic to the tropics.

There was a one hundred and sixty percent increase in blueberry consumption among United States consumers from 1994 to 2003. There are eight hundred and twenty-four thousand tonnes of blueberry produced yearly. The United States of America is the largest blueberry producer in the world, with about three hundred thousand tonnes of production per year. Besides, Canada comes second with around one hundred and seventy-six tonnes of the yearly output. The United States of America and Canada produce more than fifty percent of the total blueberry in the world.

Horticulture and cultivation

Blueberries have lower nutrient requirements than most crops because they have a shallow root system. They thrive in acidic soils, with pH ranges from 4.5 to 5.5, with limited availability of essential nutrients such as nitrate nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Blueberries prefer substrates like sandy-loam soils with high percentages of organic matter, and sometimes sulfur is added to the substrate to lower the pH.

Many new fields are irrigated through drip systems. A significant advantage of drip irrigation is the ability to fertilize apart from less water in the system. The blueberry root system is not only shallow but also has a limited water uptake capacity. Most of the roots of a drip-irrigated plant are located near the drip emitters, and therefore, nutrient application through the drip system is a very efficient way to apply the fertilizer. Several advantages of fertigation include reduced delivery costs, greater control of where and when the fertilizers are placed, the ability to target the application of specific nutrients during a particular stage of crop development, and the potential to reduce fertilizer losses by supplying only small amounts of fertilizer to the plants as needed.

When young, the leaves are bright green, often leathery, and sometimes coppery red. Their edges can be toothed or smooth. Six to ten millimeters small bell-shaped flowers, pale pink, white, purple, or red, appear in late spring or early summer. The flowers are self-fertile, with the degree of self-fertility varying among cultivars, but highbush blueberry greatly benefits from cross-pollination. Their primary pollinators are honeybees, bumblebees, and solitary bees. Vaccinium species are generally frost-hardy and shade loving. There are many forms, such as dense and thicket-like shrubs. The plants need a light environment, acidic, well-drained soil with plenty of humus, and regular watering, whereas some prefer the boggy ground. Blueberry seeds can be germinated in about one month.

In addition, it can be propagated by division or from the cuttings in the fall. Each shoot may have one to several flushes of growth during the season. Hardwood cuttings are the best method to propagate because they can be kept in cold storage from 1.7 to 3.3 degrees Celsius for up to ninety days at nearly one hundred percent relative humidity. Alternatively, tissue culture can propagate the plantlets at a mass scale.

Disease, pest, and postharvest management.

Blueberries can have three or more growth flushes per year, the first being the most vigorous. Therefore, plants should be pruned once during the growing season and once during the dormant season. This promotes branching, increasing the number of canes that will produce fruit in the future. Pruning improves the aeration between the tree canopy, reducing the chances of infection and pest infestation.

Blueberry suffers from blueberry aphids (Illinoia pepperi), the vector blueberry shoestring virus among production stock when feeding on foliage. Then, several caterpillar pests such as bagworms (Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis Haworth), azalea caterpillars (Datana major Grote & Robinson), yellownecked caterpillars (Datana ministra Drury), eastern tent caterpillars (Malacosoma Americanum Fabricius), fall webworms (Hyphantria cunea Drury), whitemarked tussock moths (Orgyia leucostigma J.E. Smith), and obliquebanded leafrollers (Choristoneura rosaceana Harris) may defoliate small canopy portions in a blueberry shrub. In addition, blueberries also face the constraint on the production by a chrysomelid leaf-feeding beetle known as cranberry rootworm, Rhadopterus picipes Olivier. Then, Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica Newman) are one of the most damaging pests that attack flowers, fruit, and foliage.

Two important pathogens attack highbush blueberry fruits: Botrytis cinerea Pers.:Fr., which causes botrytis blossom blight, and Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi Honey, which causes mummy berry disease. Blueberry anthracnose, caused by Colletotrichum acutatum Simmonds can affect the postharvest fruit quality of highbush blueberries. Then, leaf pathogens like Septoria albopunctata Cooke, Gloeosporium minus Shear, and Dothichiza caroliniana Demaree & M.S. Wilcoxis will reduce photosynthesis in the infected leaf tissues, specifically inducing premature defoliation. The leaf pathogens will affect the flower bud formation subsequently. Moreover, a powdery agent (Microsphaera vaccinii) is present at economically insignificant levels in most blueberry orchards in the United States, but has not yet been reported in other countries.

Furthermore, common diseases like cankers and stem blight are also found in blueberry cultivation. Viruses such as blueberry scorch virus (sheep pen hill disease), blueberry shock ilarvirus, blueberry shoestring sobemovirus, tobacco ringspot virus, tomato ringspot virus, peach rosette mosaic virus, and blueberry leaf mottle virus are common viruses that found in blueberry cultivation. Blueberry shoestring sobemovirus is the most widespread virus disease of highbush blueberry.

The potential quality of the fruits will never increase after the fruit has been picked. Therefore, the maximum quality and storage life of the fruit has been determined at harvest. Furthermore, harvesting practices markedly influence the blueberry quality and storability. The machine harvested fruit was ten to thirty percent softer and, when held for a week at twenty degree Celsius, had eleven to forty-one percent more decay. Fifty times as many canes were damaged by mechanical and hand harvesting. It is labor-intensive and requires up to ten pickings by hand during the harvest season.

Besides, blueberry shelf life can be prolonged by sorting and placing them in cold storage for either long storage or processing by hydrocooling technology with the addition of sodium hypochlorite solution at the optimum storage temperature of zero degree Celsius immediately after being harvested to reduce respiration and fruit dehydration.

Nutritional facts

Blueberries are spherical or semispherical or semispherical, tiny, soft, and sweet blue fruits ranging from 0.7 to 1.5 centimeters in diameter. These fruits can be consumed without peeling or cutting and contain glucose and fructose. Blueberries were popularized as a “super fruit” due mainly to their high antioxidant activity and abundant bioactive compounds. Despite the benefits of blueberries, they are seasonal fruit. Lowbush blueberries are typically grown for processed blueberries used in baked goods, yogurts, and fresh and processed organic fruit. Highbush blueberry fruit is used fresh and frozen for use in processed foods.

In countries that are large blueberry producers, blueberries not intended for fresh consumption are most often frozen in fluidized tunnel freezers. In the world markets, fresh blueberries are sold in retail packages, and frozen blueberries are sold in bulk packages. The latter, as half-products, are used for processing, that is, for making jams, conserves, or juices. Fruit collected by machine is sorted and stored, and most of it is later sold for industrial processing. The advantage of such a procedure is the effective use of almost the entire crop. Even unripe and defective fruit can be processed. Healthy but damaged fruit is processed as an ingredient for yogurts or ice creams, whereas unripe fruit is treated as a source of selected biologically active compounds.

Generally, blueberries in a fresh form consist of water (84%), carbohydrates (9.7%), proteins (0.6%), and fat (0.4%). The average energetic value of a 100-g serving of fresh blueberries is estimated at 192 kJ. Blueberries are a good source of dietary fiber that constitutes 3% – 3.5% of fruit weight. Besides the taste, the main interest in this fruit is due to the moderate vitamin C content and other vitamins like vitamins A, D, and E. One hundred grams of blueberries provide, on average, 10 mg of ascorbic acid, which is equal to 1/3 of the daily recommended intake. Moreover, blueberries have bioactive compounds such as flavonoids (especially anthocyanins), tannins, and phenolic acids, as well as various beneficial health properties attributed to blueberries.

In addition, blueberry is a good source of anthocyanins as the color change from reddish purple to dark blue according to the accumulation of anthocyanins derived from a particular anthocyanidin type. The color pigments in blueberries (red, blue, purple) are glycosides of cyaniding, delphinidin, and pelargonidin, respectively. The anthocyanins in blueberries provide their red, blue, or purple color. According to the groups of donor electrons (methoxy or hydroxyl) that bind to the aglycones, anthocyanins are the aglycone form of anthocyanidins. In addition, five anthocyanidins are found in blueberries—delphinidin, malvidin, petunidin, peonidin, and cyaniding. Blueberries exclusively have procyanidins, considered one of the major phenolic compounds in the fruit pulp (tannins). Additionally, compared to other nutrients in fruit, the anthocyanin content in the waxy outer layer of blueberries is high, indicating that the nutrient quality of the fruit as a functional food is also high. This is because consumers prefer blueberry fruits with clearly distinct or dark colors, as they believe they contain many compounds that provide health benefits.

Apart from that, blueberry anthocyanins are well known as potent natural antioxidants, but they also reduce inflammation, particularly in the gut, and protect against cardiovascular disease development by attenuating systemic microinflammation. Additionally, the anthocyanin of the blueberry aids in vision improvement apart from having antibacterial, neuroprotection, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity agent, antiglycemic, neuroprotective, ophalmoprotective, prebiotic, and antioxidant activity.

Furthermore, dietary blueberries allegedly enhance vision and brain function by enacting an anti-inflammatory role to attenuate projected chronic diseases (such as obesity and diabetes) simply through a prebiotic part that favorably regulates the gut microbial population. The food industry also investigated the potential of anthocyanins as natural dyes, as concerns about the potential adverse effects of synthetic dyes have increased. The stability of anthocyanins in food and drink can be improved using a derivatization protocol that polymerizes anthocyanins and creates stable-colored by-products.

In fact, blueberry juice is one of the most widespread blueberry products and is demanded by consumers because it has an attractive taste and preserves the most nutrients from fresh fruit. Blueberry juice can be made from fresh and frozen berries using a juice squeezer, and then the juice can be clarified. Subsequently, it must be filtered and pasteurized to obtain a microbiologically stable food product with an attractive color, a quality property appreciated by consumers.

On top of that, the anthocyanins in blueberry pomace were used as a natural colorant to dye cotton. Fruit color depends on components on and within the peel of the fruit. The blue skin results from pigments and anthocyanins, which are produced at the onset of ripening. Blue color development in white and pink fruit can take place off the bush, but the sugar accumulation associated with maturation will not occur in this case. Berry growth is limited after the blue stage is reached, but sugars and flavor volatiles continue to increase. Therefore, blueberry fruit obtains its optimal eating quality when allowed to remain on the plant for a few days after turning full blue.

Cranberry

Vaccinium macrocarpon (syn. Oxycoccus macrocarpon)

It is referred to as American cranberry under the family of Ericaceae, native to Eastern North America. Cranberry breeding has undergone relatively few breeding and selection cycles since domestication in the nineteenth century. The recent development of genomic resources in cranberry will provide for innovative plant breeding systems that will reduce the time and field space required and facilitate the breeding of unique superior cranberry cultivars to meet the current and future challenges of this crucial American crop. This evergreen is commercially grown there, and several cultivars are known. Prostate in habit, it forms mats of interlacing wiry stems with alternate leaves spreading to around three feet when fully mature. They produce pink and nodding flowers in summer, followed by relatively large and tart red fruit.

Horticultural practices

Unlike the deciduous blueberry plants, cranberries are perennial evergreen dwarf shrubs (up to 30 cm in height). Two species are commonly cultivated: V. oxycoccos L. (commonly known as a sour berry) in Europe, Asia, and some parts of North America, and V. macrocarpon Aiton in the United States, Canada, and Chile. Cranberry shrubs grow in wetlands that produce horizontal runners covering the soil. From the runners, vertical shoots called uprights to grow and produce flowers in terminal mixed buds. Like blueberries, cranberries require acidic soil and are well adapted to nutrient-deficient soils; however, nitrogen supplementation significantly impacts plant growth and fruit yield more than pH alone.

In nature, cranberry reproduces both sexually and asexually through stolons. Stolon sections are in contact with soil roots readily. Ascending shoots colloquially referred to as “uprights,” are produced along the length of the stolon and are terminated by an inflorescence bud. Typically, inflorescence buds are initiated in late summer and early fall, remaining dormant through winter. Cranberry is an asexually propagated crop, with varieties typically being propagated from material collected from producing commercial beds. They were pruning the bed yields largely stolons while mowing the bed yields both runners and uprights. These traditional propagation methods have resulted in compromised varietal identity and problems with genetic heterogeneity common place. Cranberry is highly self-fertile, necessitating emasculation three to five days prior to anthesis. Pollen sheds with minimal agitation through terminal poricidal openings. In addition, cranberry requires hymenopteran pollinators, and most commercial beds utilize honeybees at about one to two hives per acre.

Cranberries are cultivated in bogs on small farms. The bogs are constructed using water-confining layers of soil and dikes that perch the water table. This is important for the harvest when bogs are flooded with thirty to sixty centimeters of water to collect fruits previously knocked off the uprights. The cranberries float to the water surface due to a small internal air pocket that reduces fruit density. This process is known as wet harvest. Then, flooding can also be used to prevent plant desiccation in winter, in which case it can last for months. Wet harvesting can result in excessive mechanical injury, negatively impacting postharvest handling. Alternatively, fruits can be dry harvested, either manually or mechanically, and these fruits are primarily destined for the fresh market. After harvesting, fruits are processed (mostly concentrated) near growing regions to reduce shipment costs and avoid postharvest losses, generating a considerable amount of press cake.

Disease, pest, and postharvest management

Fresh cranberry fruit quality is based on color, size, and texture. Fruit should have intense red color, surface shine, uniform size, good firmness, and freedom from defects. The flesh should be creamy white. Fruits are stored in bulk storage containers generally comprised of wood flats or pallet-sized storage containers with depths of about six inches. After storage, the fruit is graded and sorted to remove defective fruit before packaging. Fruits are typically marketed in perforated polyethylene bags of various sizes. Less frequently, the fruit may be put into plastic clamshells or fruit baskets. Bags or fruit containers are placed into corrugated cardboard cartons for shipment and marketing.

The leading causes of fruit loss during storage are decay, physiological breakdown, and physical damage. Decay of fruit in storage is caused by a complex of fungal organisms, including black rot (Allantophomopsis lycopodina, A. cytisporea, and Strasseria geniculata), ripe rot (Coleophoma empetri), end rot (Coleophoma empetri), berry speckle (Phyllosticta elongata), blotch rot (Physalospora vaccinii), and yellow rot (Botrytis spp.). Infection of the fruit is believed to occur during bloom or wet harvest in the case of fungi causing black rot. Decay is typically characterized by discoloration and softening of the fruit. Rotted cranberries generally have external lesions; often, only part of the inner flesh is red, while the unaffected flesh remains white. Unlike many postharvest decays in other crops, there is little spread of disease from infected to healthy fruit in storage.

In addition, the physiological breakdown has also been referred to as sterile breakdown because there is no association with a fungal pathogen. The physiological breakdown is characterized by a dull appearance, rubbery texture, and diffusion of red pigment throughout the fruit flesh. The breakdown can result from chilling injury due to low temperature storage. Adequate ventilation to maintain lower relative humidity with high ventilation is beneficial to extend cranberry fruit storage life. Many cranberries are stored in unrefrigerated buildings where fruit temperatures vary during storage depending on ambient conditions. However, refrigeration to maintain a constant temperature can reduce storage losses. Precooling is the rapidly removing heat from freshly harvested produce to reduce respiration, retain fruit quality, and slow the development of decay.

Furthermore, there are several postharvest treatments for lengthening the life shelf of cranberry. Short treatments using hot water or hot air can reduce the decay and spoilage of fresh commodities during storage by killing pathogens or altering the physiology of the product. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation kills microorganisms and can induce resistance to decay in some fresh fruits and vegetables. Fumigation treatments have not been effective in prolonging cranberry storage life.

Nutritional facts

Raw, unsweetened American cranberries contain mainly 87% water and 12% carbohydrates, with less protein, fats, and fiber. Fresh cranberry fruit quality is based on color, size, and texture. Citric, malic, and quinic acids were the primary acids found in the large cranberry. Cranberry fruit is an essential source of antioxidants, such as polyphenols (flavonoids, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, tannins), ascorbic acid, and triterpene compounds. Fruit should have intense red color, surface shine, uniform size, good firmness, and freedom from defects. Cranberry fruit is acidic in nature, and it can involve unwanted bacteria in the urinary tract. Cranberry is rarely consumed fresh due to its tart and astringent taste. It is chiefly consumed as processed juice (sixty percent) and, to a lesser extent, as sauce and sweetened dried fruit.

Cranberries are a valuable source of biologically active substances with well-known health benefits. They contain vitamins (C, A, B1 and B2), microelements (potassium, calcium, sodium, phosphorus, magnesium, iron, iodine, pectins, and dietary fibre), and organic acids to different chemical groups. Cranberry flavonols mainly consist of quercetin glycosides, myricetin, and kaempferol (to a lesser extent). In the cranberry fruits, anthocyanins have been determined as a significant group of polyphenols, including glycosides of the 6 aglycones of the anthocyanidin family: cyanidin, peonidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, delphinidin, and petunidin.

As fresh cranberries are hard, sour, and bitter, about ninety-five percent of cranberries are processed and used to make cranberry juice and sauce. Cranberry juice is often sold as a herbal supplement. There are no regulated manufacturing standards, and some marketed supplements are contaminated with toxic metals and other drugs. Herbal or health supplements should be purchased from a reliable source to minimize the risk of contamination.

Consuming cranberries can prevent tooth decay and gum disease, inhibit urinary tract infections, reduce inflammation in the body, maintain a healthy digestive system, and decrease cholesterol levels. Cranberry helps treat cardiovascular diseases, improving the lipid profile, and minimizing the likelihood of atherosclerosis by decreasing low density lipoproteins, reducing blood pressure, increasing high density lipoproteins (good) and preventing metabolic syndrome. Cranberry is effective against all inflammatory processes, and now it is known that even cardiovascular and oncology diseases lead to inflammatory responses.

There are other species of the same genus:

Vaccinium arboreum

It is a tree sparkleberry, also known as farkleberry, which is Southeastern USA, this medium to large deciduous or semi-evergreen shrub can achieve tree-like proportions in the wild. Its glossy, dark green leaves are two inches long and leathery with downy undersides. The foliage colors well in fall, but the berries appeal as food only to birds.

Vaccinium corymbosum

This deciduous species, commonly known as highbush blueberry from New England, the USA, prefer boggy soils. Traditionally, Northern highbush blueberry fields have been fertilized using granular fertilizers.

It is grown mainly for its edible, blue-black berries. It also displays delicate scarlet autumn foliage. Forming a dense thicket of upright stems with a height and spread of six feet, its new leaves are bright. The clusters of pendulous flowers are pale pink. Blueberry ‘Blue Ray’ has delicious, sweet, juicy fruit, whereas ‘Earliblue’ is tall and vigorous with huge berries. For heavier cropping, most farmers grow two cultivars together.

Vaccinium cylindraceum

It is a deciduous or semi-evergreen, medium-sized shrub native to the Azores. It has dark green, glossy, finely toothed leaves and produces flowers in short, dense racemes on the shoots of the previous year. The flowers are cylindrical and about and about twelve millimeters long. The flower buds are red and turn into pale yellow-green when they open and are produced in summer and fall. They are followed by cylindrical blueberries covered with a bloom.

Vaccinium glaucoalbum

This evergreen shrub has a suckering habit and occurs naturally in the Himalayas. It reaches two to four feet in height. The large, oval, leathery leaves are mid-green and vividly blue-white beneath. The tiny cylindrical flowers, white flushed pink with silvery white bracts, are produced in racemes in early summer. The berries are black with a glaucous bloom and often last well into winter. It prefers a moist and shaded position.

Vaccinium myrtillus

This species is known as bilberry or whortleberry, which is found in European and North Asia. It is a compact and semi-deciduous shrub around eighteen inches tall. It has small oval leaves with finely toothed edges and spring bears ranging from six to twelve millimeters wide with dusky red, bell-shaped flowers. Edible blue-black berries follow. This tough little shrub is ideal for rock gardens.

Vaccinium ovatum

This evergreen huckleberry occurs naturally from Oregon through to Southern California, this is a dense and compact shrub. Its dark green and glossy foliage is much in demand by florists as it lasts well in water. This demand has driven wild plants very nearly to extinction. The plant forms three feet, spreading clump high and five feet wide, and can reach eight to ten feet in shady spots. The white or pink flowers appear in early summer. Its tangy and edible berries are red when young, but turn to blue-black in maturation.

Vaccinium vitis-idaea

Cowberry or foxberry is native to North America, Europe, and Asia. This vigorous, evergreen, prostrate shrub will form six to twelve inches high hummocks. The small, dark green, leathery leaves become bronzed in winter. Its flowers are bell-shaped, white, tinged pink, and borne in short terminal racemes during summer. The globular red berries are produced in late autumn and are edible but acidic to the taste. ‘Koralle’ is an incredibly abundant cropper that has won the Award of Garden Merit from the Royal Horticultural Society in the United Kingdom.

Further readings:

Blumberg, J. B., Camesano, T. A., Cassidy, A., Kris-Etherton, P., Howell, A., Manach, C., Ostertag, L. M., Sies, H., Skulas-Ray, A., & Vita, J. A. (2013). Cranberries and their bioactive constituents in human health. Advances in Nutrition, 4(6), 618-632.

Celli, G. B., & Kovalesk, A. P. (2019). Blueberry and Cranberry. In Integrated Processing Technologies for Food and Agricultural By-Products (pp. 165-179). Academic Press.

DeMoranville, C. J. (2010). Nutrient management in cranberry production.

Forney, C. F. (2003). Postharvest handling and storage of fresh cranberries. HortTechnology, 13(2), 267-272.

Hall, H. K., & Funt, R. C. (Eds.). (2017). Blackberries and their Hybrids. Crop production science in horticulture (Vol. 27). CABI.

Nemzer, B. V., Al-Taher, F., Yashin, A., Revelsky, I., & Yashin, Y. (2022). Cranberry: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Impact on Human Health: Overview. Molecules, 27(5), 1503.

Press, T. (2015). Homegrown Berries: Successfully Grow Your Own Strawberries, Raspberries, Blueberries, Blackberries, and More. Timber Press.

Retamales, J. B., & Hancock, J. F. (2018). Blueberries (Vol. 27). Cabi.

Vorsa, N., & Johnson-Cicalese, J. (2012). American cranberry. In Fruit breeding (pp. 191-223). Springer, Boston, MA.

Vorsa, N., & Zalapa, J. (2019). Domestication, genetics, and genomics of the American cranberry. Plant Breeding Reviews, 43, 279-315.