Citrus is a famous fruit under the family Rutaceae and is one of the most pivotal fruit crops in the world as it is rich in vitamin A, C, and E as well as minerals, flavonoids, coumarins, limonoids, carotenoids, pectins, and other compounds. In addition, they are well-accepted through fresh fruits or their derived product by consumers of all over the world because of their attractive colors, pleasant, and aroma. Citrus is now widely grown in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world. The annual production of the citrus is about 102 million tons.

The exact number of original wild species in this genus of evergreen small nonclimacteric trees, originally native in the Southeast Asian region, is very uncertain as many of the cultivated forms are probably of ancient hybrid origin after their domestication, which took place mainly in China and India. While largely cultivated for their fruit, citrus plants have the bonus of looking attractive in the garden, with glossy evergreen leaves and fragrant flower.

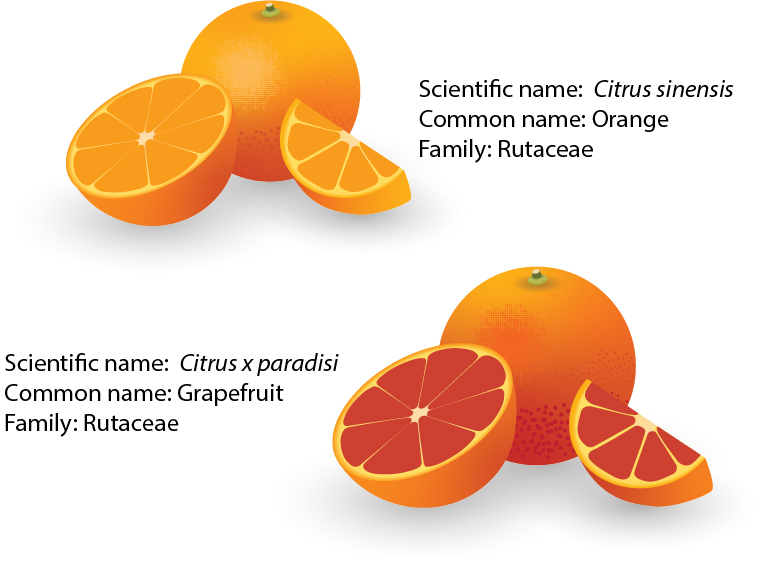

Citrus sinensis

Orange is a hybrid between pomelo (Citrus maxima) and mandarin (Citrus reticulata). It is an attractive tree that can grow up to 25 feet tall, with a rounded head, glossy foliage, and sweetly scented white flowers. Oranges originated in Southern China, Northeast India, and Myanmar, and can be grown in most non-tropical climates. Orange trees are tolerant of very light frosts.

Oranges are classified as hesperidia resulting from a single ovary, which is a type of berry with multiple seeds and fleshy pulp. The fleshy juice sacs accumulate sugars, organic acids, and a large amount of water. Generally, they contain sufficient amounts of folacin, calcium, potassium, thiamine, niacin, and magnesium, as well as high levels of antioxidants. Brazil is the largest orange-producing country, producing about 16.9 million metric tons per year.

‘Valencia’ is the most frost-hardy of all oranges, producing small and tangy fruit in spring and summer that is most commonly juiced but can also be eaten fresh. It contains minimal seeds compared to other varieties, with each orange usually containing between one and nine seeds. It is an excellent variety for obtaining high-quality juice that will last for days in the fridge and remain sweet and delicious.

The ‘Navel’ orange is a mutation of forms with a ‘navel’-like button at the fruit apex and contains no seeds. It is also considered to be one of the best oranges for juicing as it is quite sweet. However, Navel orange juice turns bitter within half an hour, which makes it the only good choice if you drink the juice immediately.

Furthermore, the ‘Washington Navel’ is another variety of orange that fruits throughout the winter and produces very large and sweet fruit. This bright orange fruit is best suited to slightly cooler areas. ‘Joppa’ is a good variety for tropical gardens. ‘Ruby Blood’ has oblong fruit with reddish rind, flesh, and juice. It is the best known and best-tasting of the ‘orange blood’ varieties. The blood-red color of this orange is due to the presence of anthocyanin in the rind and flesh of the fruit. The red color develops with warm days and cool nights, making it suitable to be planted in Mediterranean climates and subtropical regions.

Oranges are rich in vitamin C, which improves body immunity, and many antioxidants and active compounds, particularly carotenoid pigments, that have antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-arteriosclerosis properties, and can help with hyperglycemia. However, the compounds in freshly squeezed orange juice are unstable; therefore, bottled orange juice requires thermal processing to reduce enzyme and microbial activity.

Oranges can be processed into juices for commercial purposes, and vitamin C can be extracted into supplements or flavor pills to cover up the bitter taste. The peels are waste which can be extracted to obtain essential oils. The orange peel can be further utilized as part of animal feed but not as a substitution, as a high concentration of orange peel can cause rumen parakeratosis (hardening and enlargement of the papillae of the rumen). The orange peel can be used as organic fertilizer through composting. Orange peels can also be processed into bioethanol, biomethane, industrial enzymes, and pollutant absorbents through biomass engineering.

The major constraints of orange production are diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Commonly observed symptoms on orange plantations are black pit and citrus blast.

Other species:

Citrus aurantium

Sour oranges, also known as bitter oranges or Seville oranges, are marginally frost-hardy small trees that are grown as ornamental shrubs or for their fruit, which is used to make marmalade and jelly. They are also commonly used as the rootstock in groves of sweet oranges.

The heavy fruiting variety ‘Seville’ is the premium marmalade orange, while ‘Chinotto’ is a variety with small, dark green leaves that is suitable for compact growth, such as planting in containers or as border shrubs. The dwarf ‘Bouquet de Fleurs’ is a more fragrant, ornamental shrub with smooth stems and showy flowers.

Citrus x paradisi

Grapefruit is easily grown in mild areas and is commonly referred to as such due to its fruit being borne in clusters like grapes. It makes a dense and rounded tree that can reach 20 to 30 feet or more in height. Grapefruit is well-known for its large, golden-skinned fruits and is considered to have the highest quality and commercial potential as a fresh fruit among citrus fruits grown in the tropics.

Grapefruits originated in the West Indies and share many characteristics with Pummelos (C. maxima). The most popular varieties are ‘Marsh’, ‘Marisson’s Seedless’, and ‘Golden Special’. The seedless and ‘Ruby’ cultivars are more tender and prefer a frost-free climate. In red grapefruit, the color is due to lycopene and is not related to vitamin A.

Grapefruit is a fruit that should be avoided when taking certain drugs and medications. This is because the metabolism of these drugs involves oxidation by enzymes belonging to the cytochrome family, which can be inhibited by the furanocoumarins present in grapefruit. It is important to seek medical advice before consuming grapefruit if you are taking any medications.

Citrus reticulata

This species is the most varied among citrus species and has a wide range of climate tolerance among its varieties. It is usually called mandarin or tangerine, and some can survive an occasional light frost. The fruit is easily peelable or has a looser skin and is deep orange to reddish-orange in color when fully mature. Most mandarins lose quality, and the rind ‘puffs’ if not picked when internally ripe. The tree can grow up to 12 to 20 feet or more and is a good fruit tree for the suburban garden. Similar to oranges, the fruit is smaller. It is slow-growing and has heavily perfumed flowers.

The peel can be consumed freshly or zested. It can also be dried into chenpi as a spice for cooking, baking, drinks, or processed into candy or used as traditional Chinese medicine.

Citrus x tangelo

Tangelo is an evergreen tree that grows with a canopy up to 20 to 30 feet high and 10 feet wide. This hybrid is derived from a cross between the tangerine (Citrus reticulata) and the grapefruit (Citrus paradisi). Tangelo is renowned for its juicing properties and as a superb dessert fruit with a tart yet sweet flavor. It can be planted in a warm site sheltered from frost.

Horticultural and cultivational practices

Most citrus species are frost tender to some degree, but a few tolerate very light frosts. Lemons are the most cold-resistant, especially when grafted onto the related Poncirus trifoliata rootstock, while limes are the least cold-resistant and do best in subtropical locations. All citrus can also be grown in pots, as long as the containers are large and the citrus trees are grown on dwarfing rootstocks.

Citrus trees require very well-drained, friable, slightly acidic loam soil as the best medium for their growth. They require full sun and regular watering, but they should be protected from wind, especially during the summer months. Regular fertilization is also necessary, with large amounts of nitrogen and potassium for good fruiting. As usual, pruning is required to remove dead, diseased, and crossing wood to reduce the growth of pests and pathogens. Citrus trees are rarely propagated by home gardeners, as this requires horticultural skills and is usually done through conventional grafting.

Pest, diseases, and postharvest management

Citrus is subject to a range of virus diseases and can be invaded by many pests, including aphids, psyllids, whiteflies, blackflies, scale, leaf miner, bronze orange bug, spined citrus bug, fruit fly, and fruit-sucking moth. Regular pruning is required to watch for citrus scab, melanose, which are dark brown spots found on the wood and fruit. Furthermore, it is commonly affected by anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides), greasy spot (Mycosphaerella citri), Alternaria brown spot (Alternaria citri), and citrus canker (Xanthomonas campestris).

Losses in orange production are usually caused by pre- and post-harvest factors. Pre-harvest factors include climatic conditions, especially relative humidity, rain, temperature, cultivation practices, tree health, stage of fruit maturity, as well as the type of fruit. Therefore, the fruit has to avoid abnormal appearances such as being shriveled, lusterless, and soft, as well as decay or rotting. The abnormalities can be reduced through proper harvesting, handling, treatments, and packaging.

Postharvest treatments such as degreening with ethylene gas, curing, wax coating, the application of growth regulators, and proper packing-line operations are common. A proper packing-line operation should include sorting upon receiving, pre-sizing, washing, grading, fungicide application, waxing, surface drying, quality grading, and sizing followed by packing in net bags or polyethylene film bags. Disinfection and cleaning can be achieved by chlorination, ozone, or ultraviolet treatment. Oranges can generally be stored for 8 to 12 weeks at 2 to 7 degrees Celsius.

Wax coating is mainly used for polishing and improving the sheen, as well as reducing water loss of citrus fruits. They are available in various forms such as solvent waxes, aqueous emulsions, and resin solutions. The term “wax” is used as a generic term for any type of coating, regardless of whether it contains wax or not. Common waxes used in wax coating are carnauba, paraffin, and oxidized polyethylene. An edible coating can be developed from proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, or from a blend of these compounds.

Further readings:

Ángel Siles López, J., Li, Q., & Thompson, I. P. (2010). Biorefinery of waste orange peel. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 30(1), 63-69.

Antonio, J., Melendez-Mart, N., Isabel, M. V., & Francisco, J. H. (2007). Review: Analysis of carotenoids in orange juice. J Food Compos Anal, 20, 638-49.

Bailey, D. G., Arnold, J. M. O., & Spence, J. D. (1994). Grapefruit juice and drugs: how significant is the interaction?. Clinical pharmacokinetics, 26, 91-98.

Das, A. K. (2003). Citrus canker-A review. Journal of Applied Horticulture, 5(1), 52-60.

Denaro, M., Smeriglio, A., Xiao, J., Cornara, L., Burlando, B., & Trombetta, D. (2020). New insights into Citrus genus: From ancient fruits to new hybrids. Food Frontiers, 1(3), 305-328.

Etebu, E., & Nwauzoma, A. B. (2014). A review on sweet orange (Citrus sinensis L Osbeck): health, diseases and management. American Journal of Research Communication, 2(2), 33-70.

Ladaniya, M. S. (2015). Postharvest management of citrus fruit in south Asian countries. Acta Hortic, 1065, 1669-1676.

Naidu, M. M. (2021). Effect of Different Organic Sources of Nutrients on Growth, Yield and Quality of Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis). Chemical Science Review and Letters, 10(39), 372-376.

Prange, R. K., & DeEll, J. R. (1997). Preharvest factors affecting postharvest quality of berry crops. HortScience, 32(5), 824-830.

Sanders, K. F. (2005). Orange harvesting systems review. Biosystems Engineering, 90(2), 115-125.

Zou, Z., Xi, W., Hu, Y., Nie, C., & Zhou, Z. (2016). Antioxidant activity of Citrus fruits. Food chemistry, 196, 885-896.