General description

Orchids are grown for the astonishing beauty and variety of their flowers. Orchids can charm and tantalize, fascinate, and be frustrating. The most beautiful orchids are the gorgeous South American cattleyas, often huge, sparkling, rosy-purple, and mauve blooms. To be specific, others have an altogether different appeal, such as having a strangely weird, sometimes evil-smiling species found among the Bulbophyllum. There are numerous delightful orchids of unlimited charm and desirability in between these two extremes. A vast number of collections is made up from among this multitude of varieties.

The common orchid often seen in homegrown situations is the delightful Phalaenopsis, softy hued, speckled or spotted, candy-striped or plain. These orchids have shot to fame in recent years and are now the most popular houseplant orchid. In the combination of white, pink, and yellow colors, phalaenopsis produces three to four attractive, dark to mid-green, broad, horizontally curving leaves with several thick and silvery-white roots with a strong tendency to meander outside their pot. These plants are ideally suited to indoor culture as the flowers will last for weeks at a time, and before the first flower spike has finished, there is often another showing at the base with the promise of other blooms in the months to come.

Furthermore, an orchid that is frequently seen gracing large open areas is the Cymbidium. These hardy orchids produce long, narrow, tropical-looking foliage that typically cascades below the blooms, carrying tall flower spikes with a dozen or more flowers. With almost unlimited colors available, there is no end to their variety, and only blue color flower has proved elusive to the hybridizer. Orchids are true epiphytes that spend their lives without contacting the forest floor. Orchids are one family of plants (Orchidaceae) that have evolved to the epiphytic lifestyle. Orchids represent the largest family of flowering plants globally, and their diversity and distribution are virtually unchallenged in the plant kingdom.

Today, there are about thirty thousand species within this global distribution, excluding hybrids. Since modern plant classification was started by the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus in 1758, taxonomists have continued to classify and reclassify existing species and describe new species. There are discoveries of orchid species from some corner of the world every year. In addition, there are about one hundred thousand artificial hybrids, and this number increases annually, as the hybridizers in the world over endeavor to meet an insatiable demand for more varieties. Due to the variations, morphologically, they are unbelievable that they can all belong to the same family of plants. This is because they are classified according to the structure of their flowers and their resemblance to one another.

Botany of orchids

Pseudobulb

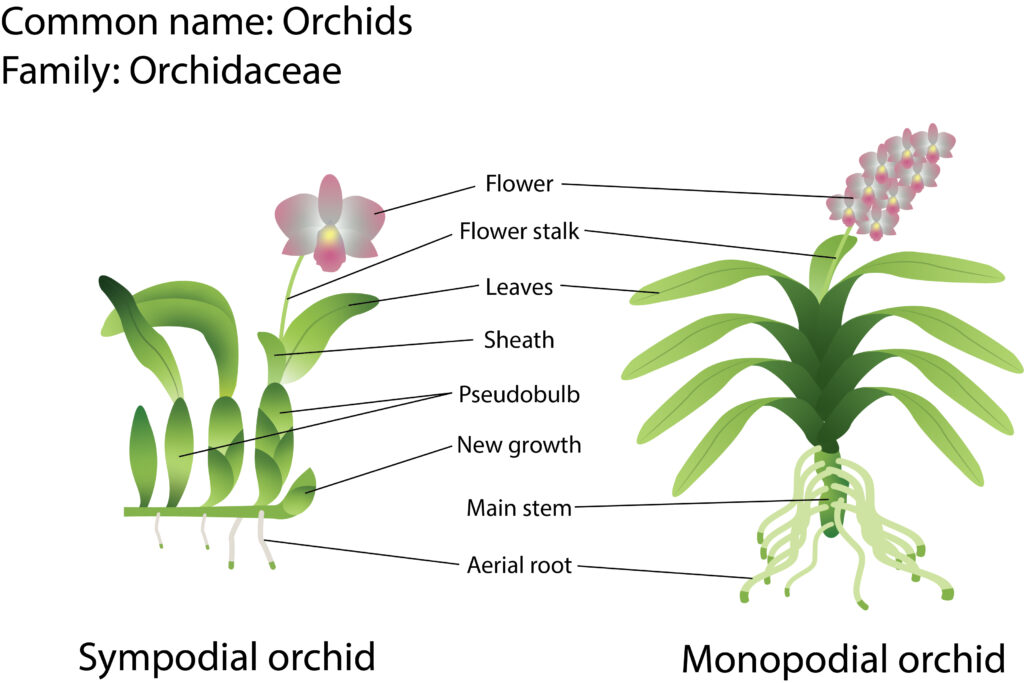

Orchids are primarily herbaceous or evergreen perennials. Many orchids develop a sympodial type of growth, where they produce pseudobulbs or false bulb that is added each season among a continually extending rhizome. Therefore, they will form large clumps that take several years. A pseudobulb consists of a fibrous material that can hold a great deal of water, which is functions to conserve energy and store moisture. Pseudobulbs are the longest-living part of the plant and will exist in a dormant state long after the leaves have been shed. The back bulb is referring the leafless pseudobulbs.

Pseudobulbs have evolved into an unlimited range of shapes and sizes, from long, thin, pencil shapes to rounded or even flattened structures. Dendrobiums produce some of the longest pseudobulbs among cultivated orchids, and these become so elongated in some species that they are called “canes”. However, some orchids possess hollow pseudobulbs, Schomburgkia tibicinis and Caularthon bicornutum. This hollow structure had defeated the purpose of storing water. However, it is found that they served a dual purpose, which is to provide a home for a species of fierce ant and keep it freed from parasites and unwanted pests.

Leaves

One of several leaves of sympodial orchids is directed produced from the pseudobulb. Different species of orchids have a different number of leaves. For instance, cymbidiums have several long, narrow leaves from the basal sheaths that cover the pseudobulb. The leaves fall from the plant at a separation line that prevents damage when the leaf is shed. Then, cattleyas produce just one or two broad, semi-rigid leaves from the apex of the pseudobulbs. In addition, monopodial orchids have a single vertical rhizome from which pairs of leaves grow at right angles. Moreover, vandas and phalaenopsis are the best representatives of monopodial orchids in cultivation.

Apart from having ‘normal’ leaves, a few orchids have no green parts. This kind of orchid relies entirely on the microscopic fungus with which they form a symbiotic relationship. Some orchids have chlorophyll roots to enable the plants to carry out photosynthesis. Furthermore, there are orchids with thick hairs on both sides of the foliage, although the mechanism is unclear. However, it is believed that the thick hairs are used to protect them from insects or prevent close contact of the water droplets with the foliage, which could be detrimental on cold nights.

Roots

The roots of orchids are unique in the plant kingdom. They are not producing the same abundance of roots as in other plants, and their roots are thick and white. The tips of orchid roots are extremely vulnerable to damage and can be easily broken when they are outside the pot. Their roots are naturally aerial and are not permanent structures but are made annually, sprouting from the base sometime after the new growth. The roots eventually die and are replaced by those from the new growth.

In monopodia, orchids like vandas have their roots made at intervals along the rhizome and seldom need to go underground. Furthermore, many orchids can photosynthesize through the roots. This important role has become the key for some leafless orchids to survive.

Flowers

While orchid plants themselves are extremely varied, they know no bounds in terms of variation in structure and color in their flowers. The flowers are so diverse and often incredibly beautiful. However, not all orchid blooms can be described as beautiful. While all orchids conform to one basic design, this has been duplicated and modified a thousand times; each variation is designed to suit the habitat or the way of growing one orchid.

One part of the flower has always become exaggerated, with petals or lips dominating the flower. All these modifications have evolved to attract a specific pollinator and to do this, and some orchids have gone to extraordinary lengths. Orchids are largely insect-pollinated. Each flower consists of six segments: three petals and three sepals. The outer three are sepals, and the inner three are petals. The third of the petals has developed into the labellum or lip, which provides an ideal landing stage for the pollinating insect. Often, the lip is lightly hinged as it functions to position the insect correctly for pollination to ensure it is the only right-size insect entering the flower.

In many orchids, the lip is large and highly colored and has a bright patterning quite distinct from the rest of the flower. There is a honeyguide, usually bright yellow ridges, at the center. Above the lip is the column that is a single and finger-like structure containing the reproductive parts of the flower. The pollen is found at the end of the column, which is usually in two, four, or six masses. The pollen-masses are golden yellow and attached to a viscid disc by two thin threads. The insects will deposit anther when it flies off, carrying the pollinia to the next bloom.

Horticultural practices

The horticultural practices on taking care of an orchid require daily spraying, weekly watering and feeding, and constant attention to growing requirements like light and warmth. Orchids are lifelong plants, and once acquired, they will live for your lifetime and beyond, provided they are not killed accidentally or weakened by mismanagement. Nevertheless, orchids will continue to bloom under the most extreme conditions, even sacrificing their own lives when a situation becomes intolerable and producing one final burst of color in a last attempt to perpetuate themselves by seed production. Phalaenopsis is unlikely to be exposed to the direct sun, caught in a cold draught, or left to freeze on cold nights. A home is a place of warmth and comfort, which suits these tropical epiphytic orchids perfectly.

Besides, Cymbidiums mostly bloom in winter and spring, bursting into flower at a time when their vibrant shades and pastel colorings are a welcome contrast to the bare gardens outside. Their blooms will remain in perfect condition for months on end. Many other orchids will also thrive indoors with the minimum of care, but a few can compare with the beautiful miltoniopsis or pansy orchids as they are affectionately known. Their small plant size and large, decorative blooms create a summer show with a delicate fragrance. Look out for these orchids and similar adaptable kinds in your local outlet and take one or two homes.

There are several tips on watering orchids. First, orchids need to dry out partially after watering once or twice a week in the growing season or once every two or three weeks while resting. Most importantly, we need to keep the plants evenly moist while growing as underwater or overwatering will cause shriveled pseudobulbs or limp foliage.

Growing orchids indoors

Orchid is known as one of the long-lasting flowers that will last for several weeks. Orchids are one of the best indoor plants as you do not have to go to any expense to provide warmth, provided there is central heating already installed in all rooms. It is easy to take care of as long as you keep a hand-held spray bottle nearby and regularly mist the leaves lightly when you pass by. To know the best location for the orchids, one must observe the colors of the leaves until the foliage shows the optimal color. The ideal aspect for summer growing is a window that receives either the morning or evening sun, but not direct sun during the hottest part of the day in summer. In the winter, most orchids will be comfortable in a well-lit window because the sun will not reach high enough in the sky to cause any problems with burning.

Growing orchids outdoor

To plant orchids outdoor, we must choose the orchids that are light-loving and cool-growing types like cymbidiums, odontoglossums, coelogynes, encyclias, and dendrobiums. Those orchids with softer and wide-leafed foliage such as lycastes, anguloas, and the deciduous calanthes would very soon become notably spoiled by blemishes because of the effects of the weather. In addition, they can be planted in a greenhouse made up of glass.

Growing media

The tropical epiphytes have evolved by growing upon the branches and trunks of trees, where their roots either hang, suspended in air, or travel along with the bark, seeking out crevices and gaining access to the humus decaying leaves in the axils of branches. Therefore, a well-drained compost or growing medium is needed to provide plenty of air around the roots. However, terrestrial orchids vary in their soil requirements. Some prefer grassy meadows with a well-drained subsoil; others like peaty bogs that are permanently wet, while in the tropics, many live on the open savanna plains where they become during the dry season completely dehydrated as the shortage of moisture in the soil.

Many orchids can be grown on bark and in a variety of compost mixes, which is known as growing media. However, regardless of the types of compost used, the main criteria are good aeration and fast drainage. Most orchids cope with their roots being cramped in a container, which provides that the compost is open and allows some air to circulate through and around the roots.

The growing media can be early organic composts, bark compost, and inorganic composts. Organic growing media like coarsely shredded bark, coconut fiber, as well as coarse compost mix containing bark and fibrous peat are commonly available at the nursery. Some will use charcoal as an organic growing media. Furthermore, there are a lot of manufactured materials that provide synthetic alternatives such as rockwool, perlite, perlag, hortag, horticultural foam. Over time, one needs to replace the compost as a bark- and peat-based composts will break down, which is why regular repotting is important.

Observations on the orchids need to be recorded, and especially when they suddenly lose much of their foliage or shrivels, they may have lost their roots, which will become apparent when you knock the plant out of its pot then examine its condition. Good compost should have a pleasant and moist smell. If it smells sour, it has probably broken down to the extent that the plant can no longer benefit from it. The compost that has deteriorated will have dissolved into small particles that will wash through to the bottom of the pot. They will clog up the drainage and cause water to stagnate.

A dense compost will make the roots can be seen to circle the rim of the pot without penetrating to the bottom, indicating that the compost is unsuitable. In addition, damp compost will cause root rot, which indirectly will kill the orchids.

Care and cultivation

Pests

Orchids suffer fewer problems compared with other plants. A good piece of advice is to keep the environment clean by removing dead leaves and other dirt from the floor to avoid fungal growth. There are not many pests to infest orchids, but generally common pests like aphids, mealybug, red spider mite, false red spider mite, scale insects as well as moss flies.

Surprisingly, bees are known as pests as they will take the pollen from the flower, rendering them useless. The flowers eventually die within one or two days if they are not intact with the pollen. Besides, mice find orchid pollen particularly attractive as a good food source. The most troublesome pests are slugs and snails. The garlic snails eat the root tips of the orchids, whereas the slugs will eat the roots and chew into new growths that often cause a great wounding in a single night. Other pests are weevils, caterpillars, woodlice, ants, and earwigs which infest the roots while ants set up their home that breaks down the compost, preventing aeration, and thus suffocating the roots.

Diseases

Abiotic stresses from overexposure to light or cold will result in disease infection. During the winter, cold and damp conditions will cause rots, molds, and blemishes to observe the orchids. Corrugated leaves are often caused by irregular watering (too wet or too dry), which is an annoying problem that occasionally arises. A cold and damp condition will damage pseudobulb, categorized as black light blotches over a long period. It can be solved by filling the infected pseudobulb with powdered fungicide at the affected areas.

Rot is one of the common diseases found in orchids. Rot in new growths must be treated before it spreads back into the main plant, resulting in a loss. Therefore, we must cut away the rotting growth until you get back to a healthy rhizome, followed by dusting the wound with fungicide or horticultural sulfur. A sunless winter will eventually cause premature spotting of flowers. This can be solved by drying out the atmosphere. On the other hand, direct exposure to the sun tends to cause a burn mark on all orchid foliage. The symptom is whitening areas on leaves that eventually turn brown and black as infection sets in.

When the orchids are cultivated in poor cultural conditions, particularly during the winter months, the abiotic stress will make the orchids weak and susceptible to viruses. However, the viruses can only be transmitted and spread through sap-sucking pests such as red spider mites and aphids. A good horticultural practice is required to ensure that the orchids are growing healthily. Removal of dead leaves and dirt, control of temperature and humidity, and the replacement of compost are important to keep the orchids healthy.

Propagation & dispersal

Vegetative propagation

Orchids can be propagated by splitting the pseudobulbs or false bulbs for those who develop a sympodial type of growth, adventitious growth. Orchids such as dendrobiums and thunias produce keikis or adventitious new growths along their length, which can be potted up and grown on. Once the keiki has a good root system, it can be separated from the parent plant using a sharp pruner. The keiki can be planted using orchid potting media and taken care of using horticultural practices.

Besides that, some orchids such as dendrobiums, thunias, and epidendrums can be propagated by taking stem sections, particularly those that produce long ‘canes’. The leafless stems are cut from the parent plant at the start of the growing season and divided into shorter lengths, each with at least two growing nodes. Then, the new growth should arise after three to four months, when the new plantlets can be potted up individually in the appropriate choice of compost for the type of orchid.

Apart from that, a pollinated orchid will produce a seedpod via pollinators like bees and wind or human. A seedpod contains extremely small and dust-like seeds that have enabled orchids to disperse and travel great distances. Therefore, a million seeds can be carried on the wind across continents and oceans; the seeds have helped orchids colonize the world.

Therefore, they are also found in even the most extreme tropical environment, dry forests. Some orchids grow in soil or leaf litter. However, millions of years of competition led most of the tropical members of the Orchidaceae into trees where the light was plentiful. This action leaves the moisture- and nutrient-rich forest floor but creates many evolutionary challenges for orchids. Once the orchids overcame obstacles inherent to life in the trees, they evolved quickly into many different genera and species on all the continents except Antarctica.

In dry forest environments, water and nutrients are supplied in pulses during unpredictable rain events. There are often extended periods of dryness between storms. Orchids adapted to these dry conditions by obtaining their water and minerals through unusual plant forms and major changes in physiology or life history.

Therefore, two general approaches to adaptation and evolution are avoidance and endurance. First, drought avoiders are seasonal growers that restrict most of their vegetative growth to wet periods of the year. Orchids in this group often have thin leaves that do not function as storage reservoirs. The dry season does not support their normal heavy water use. Therefore, the foliage is shed, and the plants lapse into dormancy. Carbohydrates and moisture are held in reserve in fat pseudobulbs, corms, or tubers. When favorable weather returns, new growths emerge from repeating the cycle. Commonly grown drought avoiders are most of the Catasetinae and certain dendrobiums and lycastes.

Plant tissue culture

Since the germination rate of the orchid seeds in nature is extremely low, close to zero when there is no specific fungus in that environment, plant tissue culture offers a great alternative to germinate the seeds in in vitro conditions. Orchid seed pods can be sterilized using a high concentration of surfactants or dipping inside alcohol then flame. The seed pod can be dissected the sow the seeds directly on the tissue culture media. This biotechnology technique is often used to germinate the hybrids that won the orchid competition. Raising orchids from seed in tissue culture jars is a modern method of propagation was performed by Noel Bernard nearly one hundred years ago. From there, the winner can apply for a patent if there are any new hybrids. Furthermore, orchids grow slowly and propagate the pseudobulbs very slowly. Orchid tissue culture is a well-known and well-developed sector for its ornamental and pharmaceutical properties.

Symbiosis

Orchids have evolved several strange associations with other living organisms. For instance, a microscopic fungus known as mycelium co-exists within the root structure of most orchids. Through this symbiotic relationship, orchid and fungus had completely dependent upon each other for survival. The mycelium will release nutrients absorbed by the orchid, which in turn becomes the host for the fungus. In addition, for a seed to germinate, it needs contact with the fungus beginning. This is because orchid seeds are tiny and have no endosperm to provide sufficient nutrients for germination. Therefore, most orchids have their specific micro-fungi, so there must exist as many different fungi as there are orchids. For this reason, orchids are often found in large colonies rather than growing as individual plants, as this proximity to other orchids ensures that the necessary fungus is present.

Adaptation and Evolution

Their far-reaching habitat has contributed to the emergence of many different species. Due to their harsh habitats, some are extremely slow-growing species. However, once they are established in large populations, they can exist for many years until they are disturbed. Tropical rainforests are found to have a diversity of orchids, which have evolved there for as long as the forests have existed.

Several different types of orchids are classified according to how they live and survive, whether trees support them, rocks, grow in the ground, and adapt to survive in different conditions. They are mainly categorized into epiphytes, terrestrials, and lithophytes. Those orchids that have evolved to live upon trees are called epiphytes. It is one of the symbiotic relationships called commensalism that brings no harm or

Epiphytic orchids anchor on the tree to get sufficient sunlight and obtain nutrients from the moisture in the air as well as any debris that has collected in the axils of the branches or beneath mosses where their roots will penetrate. Decomposing leaf litter and bird or animal droppings will make up the remainder of their meager diet. Moreover, a few orchids, such as Catasetum species, are saprophytic living upon decaying trees, where their roots penetrate the softer tissue beneath the bark. Their lifespan is more limited than epiphytes, as dead trees in the tropics will remain for only a few years before fungi and termites take their toll.

Subsequently, the orchids that grow in the ground and almost all of the terrestrial orchids had adapted in diverse places like hot and dry Australian deserts, shadier and gentler climates of temperate woodlands and grasslands, as well as cool forests. Terrestrial orchids may be in solitary splendor or just a few in a ground-level colony. Their root system penetrates deep into the soil to find moisture and nutrients.

On top of that, the type of orchids that performs a balancing act somewhere between the epiphytes inhabiting the trees and the terrestrials in the soil is categorized as lithophytes. These orchids make their homes on rocky cliff faces, sometimes on near-vertical slopes where the conditions are too extreme for much other plant life. Commonly, they are found at the limestone cliffs near the seashore or moss-covered rocks where there is some protection for the roots. Any small crevice will be the point for these lithophytes to hold and cling on with their strong roots. The inaccessibility of some lithophytic habitats has allowed a few noteworthy orchids to remain undiscovered until recently, being detected only from the air.

Similarly, lithophytes obtain nourishment like epiphytes, which rely upon regular mists and rain for moisture, but lithophytes also must withstand a long period of extreme dryness during draught. They can get the extra moisture and nutrients from crevices in the rocks or underneath the mossy covering through their roots.

To survive in the extreme natural environment, orchids will lose their leaves together with the trees when their hosts had shed the leaves to prevent dehydration due to the exposure to direct sunlight. Apart from that, orchids have evolved their survival methods by having water-storing organs such as pseudobulbs and aerial roots, which absorb the moisture that surrounds them to cope with the extreme conditions of wet-dry periods.

Surprisingly, orchids are found at all altitudes, which already adapted to their surroundings and being completely at home. Forest and tree cover differ, depending upon the altitude, and so do the growing conditions they provide. At sea level, forests are dense and lush, with little sunlight penetrating, while higher-up trees begin to thin until the higher, dryer mountain slopes are reached, which offer very little protection from the elements.

Generally, shade-loving orchids such as the phalaenopsis are nearer to sea level. Their wide succulent leaves are designed to catch as much light as possible in areas of dense forest shade. Next, at the other extreme, epiphytic lycastes often grow on the undersides of tree trunks leaning over water courses in heavily shaded areas. Therefore, their leaves have become broad and softly textured to gain the maximum benefit from the meager available light.

On the contrary, temperate forests cannot host epiphytes in the same ways as in the tropics as exposed aerial roots would soon succumb to the cold. Orchids that grow in temperate regions are mostly terrestrial, smaller, and less flamboyant in appearance than the tropical epiphytes. It is known that Orchids in Europe dislike disturbance to land and cannot thrive in fertilized fields once established. Therefore, many orchids have died out in meadows in which they had been growing in their thousands up to one hundred years ago, which have now been developed or cultivated. The orchids in Europe colonize the hillsides, and they thrive on the rocky mountainous slopes. They have colonized at the foothold at the edges of newly constructed roads that are nutrient-poor soil, which cannot support many other flowering wild plants.

Conservation

Today, orchids are traded for various purposes and at many different scales from commercial trades to subsistence use like medicines, materials for weaving, ornaments, food, and dyes. Furthermore, some orchids are harvested to be commercialized in perfumes and cosmetic products. They are often being traded legally as ornamental plants in horticultural and floricultural trade that involves several distinct types of markets and consumers. In addition, orchids are subject to exceptional levels of legal protection, including wide protections from the pressures of international trade and national legislation in many countries that further restrict their harvest from the wild that will cause the extinction of the species. This prevalence and diversity of orchids trade are remarkable because orchids are among the best-protected plant taxa globally. The CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a multilateral environmental agreement that regulates the international movement of species that are or may become threatened due to international trade. The species of concern are more than thirty-five thousand currently listed species.

The conservation challenges are that trade is often associated with unsustainable or illegal forms of harvest and trade. Besides, there are shifting patterns in the behavior of the people (consumers and intermediaries) involved in the orchid trade. Another hindrance could be the taxonomic complexity of the Orchidaceae, which presents management challenges for the identification of the species.

To prevent the extinction of endangered species, we should try to isolate the endangered orchids before deforestation. Then, we cultivate and propagate them through tissue culture to conserve the species. If we leave the orchids alone in the wild, they will become extinct due to illegal harvest by orchid hunters, infestation by pests, or die due to the infection of diseases or unable to adapt the climate change.

Further readings:

Rittershausen, W., & Rittershausen, B. (2001). gardener’s guide to growing orchids. David & Charles.

McHatton, R. (2011). Orchid pollination: exploring a fascinating world. Orchids, 80(6), 338-349.

Hinsley, A., De Boer, H. J., Fay, M. F., Gale, S. W., Gardiner, L. M., Gunasekara, R. S., … & Phelps, J. (2018). A review of the trade in orchids and its implications for conservation. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 186(4), 435-455.

Mchatton, R. (2019). Orchids-The bulletin of the American orchid society. Vol. 88, No. 4.

WONG, C. (2019). SPIKE.